H.M. The Man with No Memory

By Gemma and Jess

Henry Molaison’s Condition

Henry Molaison suffered a brain injury at the age of 7 which began a lifetime of severe epileptic seizures which worsened over time. By the time he was 20, he was having uncontrollable grand mal attacks (health threatening seizures) and it was at this point doctors decided to attempt a brain operation of which may cure his epilepsy.

The Operation

This brain operation was one of high risk. It involved removing and altering parts of the brain that the doctors believed were causing these life threatening seizures, however the consequences of these actions were catastrophic.

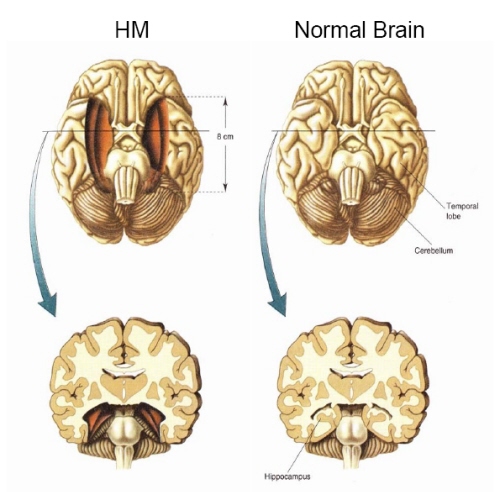

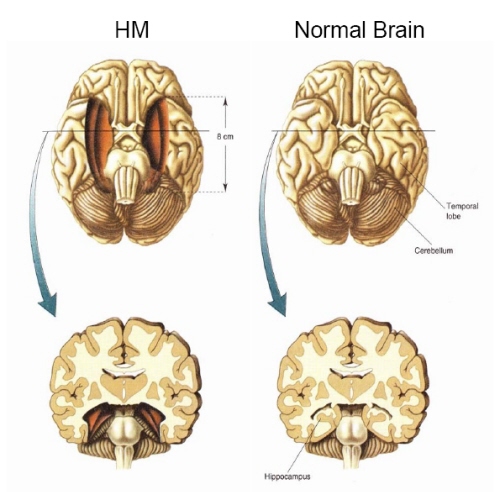

The doctors during the operation removed a part of the brain called the hippocampal region of the brain, of which house several memory circuits, however doctors did not know this at the time. Along with extensive damage to the inner part of the temporal lobes which was also caused by the operation, Henry woke up from the operation suffering from amnesia and severe memory loss.

However given that this was a result of an operation and not a brain disease, this was a very pure form of amnesia, meaning every other intellectual function in the brain was intact. So whilst Henry had no capacity to remember things, his IQ was still above average and he still possessed his language and perceptual skills. This made Henry a very unique case for neuroscientists to study, and he was a research participant from the day before his operation in 1953 until he died in 2008.

However given that this was a result of an operation and not a brain disease, this was a very pure form of amnesia, meaning every other intellectual function in the brain was intact. So whilst Henry had no capacity to remember things, his IQ was still above average and he still possessed his language and perceptual skills. This made Henry a very unique case for neuroscientists to study, and he was a research participant from the day before his operation in 1953 until he died in 2008.

What we learnt from Henry

Henry’s case brought on three major scientific discoveries regarding cognitive functions. The first of these was that memory was compartmentalised, and that memory is processed by specialist brain circuits. This effectively means a person is able to have no capacity for memorising information, and yet still be highly intelligent. The second is that the hippocampal region is essential for the ability to store long term memory, which was learnt though the consequences of Henry’s operation. It told us the hippocampus and the cortex surrounding it are where new memories are formed, and this ability to memorise information is localised to only this area. The third discovery it provoked was that not all kinds of memory or learning are affected by amnesia; there are different kinds of

memory in different locations in the brain. This idea began with a study by Brenda Milner in 1962 and since then studies like this have cemented the idea of multiple memory circuits.

Types of long-term memory:

From H.M. scientists were able to identify and differentiate two key types of long-term memory in the brain.

- Declarative (explicit) – This type of learning occurs with awareness, and is the conscious retrieval of events that occurred at a specific place or time. It is also associated with the conscious retrieval of facts such as general knowledge to the extent at which you can state what you know.

- E.g. you are able to state what you had for dinner last night.

- Non-declarative (implicit) – This is a non conscious type of memory storage, in which we demonstrate what we remember through the performance of a task. You learn without awareness and simply show off what you know when completing everyday tasks.

- E.g. riding a bike or playing tennis.

What Henry could/couldn’t do

Henry’s declarative learning was severely impaired. This meant that when test stimuli were verbal in testing his episodic memory, his severe impairment in doing so was very apparent. For example, when attempting to recall features of a short story he heard, his immediate score was 4.5 out of 23 points, which fell to 0 out of 23 after just an hour. His deficit in this area was also clear when using visual stimuli, his ability to recall a drawing was incredibly poor.

As well as his episodic memory being impaired, his semantic memory capabilities were also poor—acquiring new facts, concepts and vocabulary. He was not successful at all in an experiment which attempted to teach him eight new words.

Henry remembered very little about his every day environment, things as simple as where his bedroom was, or what clothes belonged to him, he did not remember. The studies and research into Henry’s condition and abilities strongly confirm that both episodic and semantic learning rely heavily on medial temporal lobe structures.

Despite his incapability with his declarative learning, Henry’s non-declarative learning was preserved after his operation. Information which he had learned unconsciously, like using his walking frame, he could remember. He learned the process of skills which had to take place for him to use the walking frame—getting up from a chair into the frame, then moving it along the floor, and then transferring from the frame back to a chair—unconsciously. However, he had no conscious knowledge of why he had to use the walker and so would sometimes forget he needed it resulting in him attempting to walk without it and falling.

Henry’s preserved learning of non-conscious tasks, like motor skill learning, shows that underlying computations depend on the brain circuits that weren’t damaged in Henry’s operation (i.e. outside of the hippocampal region.)

Knowing Henry

By talking to the people who Henry went to high school with, researchers were able to confirm that his operation and brain damage did not affect his personality. They all described him the same way that the scientists who knew him closely remember him, as a gentleman, who was quiet and kept to himself but was polite and gentle with a great respect for women. When asked about how he felt about taking part in all the tests that he did, he would respond saying that he is happy to do whatever he can to help other people. So although he had no conscious knowledge of what was ‘wrong’ with him, he knew that the lab that he visited and the tests which he took part in were for research that could benefit others.

that the scientists who knew him closely remember him, as a gentleman, who was quiet and kept to himself but was polite and gentle with a great respect for women. When asked about how he felt about taking part in all the tests that he did, he would respond saying that he is happy to do whatever he can to help other people. So although he had no conscious knowledge of what was ‘wrong’ with him, he knew that the lab that he visited and the tests which he took part in were for research that could benefit others.

Ethical considerations for this study

‘Is this ground breaking science or cruel exploitation of a man whose life was ruined by experimental surgery?’ Henry was not aware of what was being done, what he was taking part in or why he was doing so because of his condition, so although he is reported to always agree to take part and followed orders indefinitely, can this really be counted as informed consent? The studies, he endured for 40 years with no complaint, but he really had no memory of anything that would give him motive to disagree to anything.

Despite the common belief that Henry’s operation was the only one of its kind, in actual fact this procedure had been carried out several times before and the results could have been reasonably expected. The surgeon had been pioneering this technique on psychiatric patients and knew the risks and the likelihood of the damage which could be caused as a result of the operation. And so, the actual procedure which Henry went under, also raises the ethical issues concerning the conduct of doctors and their monitoring by their colleagues.

However given that this was a result of an operation and not a brain disease, this was a very pure form of amnesia, meaning every other intellectual function in the brain was intact. So whilst Henry had no capacity to remember things, his IQ was still above average and he still possessed his language and perceptual skills. This made Henry a very unique case for neuroscientists to study, and he was a research participant from the day before his operation in 1953 until he died in 2008.

However given that this was a result of an operation and not a brain disease, this was a very pure form of amnesia, meaning every other intellectual function in the brain was intact. So whilst Henry had no capacity to remember things, his IQ was still above average and he still possessed his language and perceptual skills. This made Henry a very unique case for neuroscientists to study, and he was a research participant from the day before his operation in 1953 until he died in 2008. that the scientists who knew him closely remember him, as a gentleman, who was quiet and kept to himself but was polite and gentle with a great respect for women. When asked about how he felt about taking part in all the tests that he did, he would respond saying that he is happy to do whatever he can to help other people. So although he had no conscious knowledge of what was ‘wrong’ with him, he knew that the lab that he visited and the tests which he took part in were for research that could benefit others.

that the scientists who knew him closely remember him, as a gentleman, who was quiet and kept to himself but was polite and gentle with a great respect for women. When asked about how he felt about taking part in all the tests that he did, he would respond saying that he is happy to do whatever he can to help other people. So although he had no conscious knowledge of what was ‘wrong’ with him, he knew that the lab that he visited and the tests which he took part in were for research that could benefit others.